Research Describes U.S. Women Who Become Gestational Carriers

As a gay intended father about to match with a gestational carrier (GC) in the U.S., it’s exciting to think of the person who may carry our baby.

I have previously written about this topic (https://www.babymoonfamily.com/original-articles/why-gestational-carrier), and I have interviewed an amazing GC who has worked exclusively with gay intended fathers (https://www.babymoonfamily.com/original-articles/stories-rachelle-myers-nelson).

However, a recent scientific study was published that surveyed and analyzed data to describe the sociodemographic characteristics and motivations of these women (1).

The lead author of the study is Dr. José Ángel Martínez-López, a Spanish academic from the University of Murica. He wanted to explore how valid the arguments against surrogacy are based on feedback from previous GCs. He summarized these anti-surrogacy arguments in three statements:

Gestating a child for others does not involve altruistic or prosocial behavior;

The women (surrogates) who agree to gestate for others are forced or coerced into agreeing and do not act freely; and

The profile of surrogates is characterized by poverty and, therefore, they are incapable of making decisions due to macrosocial factors that put them in a situation of social vulnerability.

In order to do this, Dr. Martínez-López and his team developed an online questionnaire that was distributed to surrogacy agencies in the United States and closed groups of surrogates on Facebook.

In reaching out to U.S. based surrogacy agencies and Facebook groups, the authors collaborated with Son Nuestros Hijos (SNH, or They Are Our Children) (https://sonnuestroshijos.com), a Spanish organization described (via Google Translate) as ‘an association of diverse families who use surrogacy as a way to access fatherhood and motherhood.’ The website also states that ‘SNH is the oldest organized group in Spain dedicated to activism in favor of surrogacy as a reproductive right. We are an independent, non-profit organization that is supported by membership fees and donations from benefactors.’

For me, it was great to learn that such an organization exists in Spain and is working to support all families through surrogacy.

Results of the Study

231 participants completed the questionnaire. Most of the respondents became surrogates for families in the U.S. (36.1%), followed by Spain (22.8%) and China (7.1%). I’m assuming the percentage of Spanish intended parents (IPs) is so high because of the collaboration with SNH for recruitment of GCs.

In terms of their sociodemographic profiles, the average age of the GCs was 35.8 years, 74.4% were married, and most were in family units with four members (31.2%).

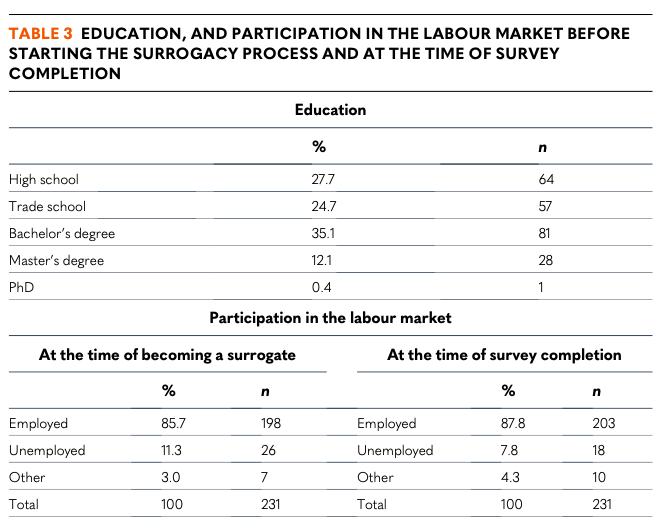

The following table shows the breakdown of education and employment status for the GCs:

Over 59.8% had completed education beyond high school (trade school or bachelors degree), and employment status actually increased from the time they became a GC to after completing their journey, going from 85.7% to 87.8% employed. This demonstrates that the majority of GCs are well-educated, and the remuneration obtained from being a GC did not discourage the respondents from working.

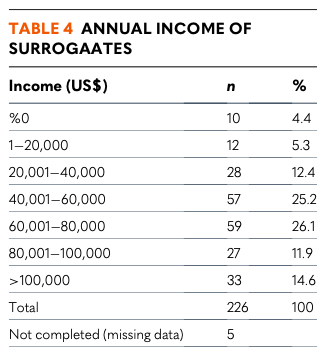

The next table shows the income ranges for the respondent GCs:

This table only shows the income of the GCs, and in 67.0% of households, two people contributed to the family finances. However, only considering the income of the GCs, 67.5% had an income above the average for their state of residency, based on StatsAmerica (https://www.statsamerica.org/).

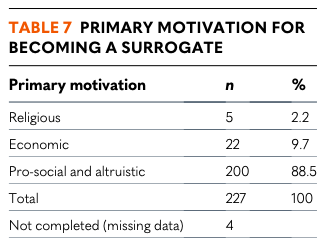

In terms of primary motivation for becoming a GC, this table shows the results from the questionnaire:

The vast majority (88.5%) stated their primary motivation for becoming a GC was prosocial or altruistic, even though they were all compensated for their journeys.

This motivation is echoed in their continued contact with IPs. 95.2% maintained contact with the intended parents, with 4.1% in contact almost every day, 30.0% were in contact almost every week, 44.1% were in contact once a month, and 21.8% were in contact occasionally (birthdays and holidays).

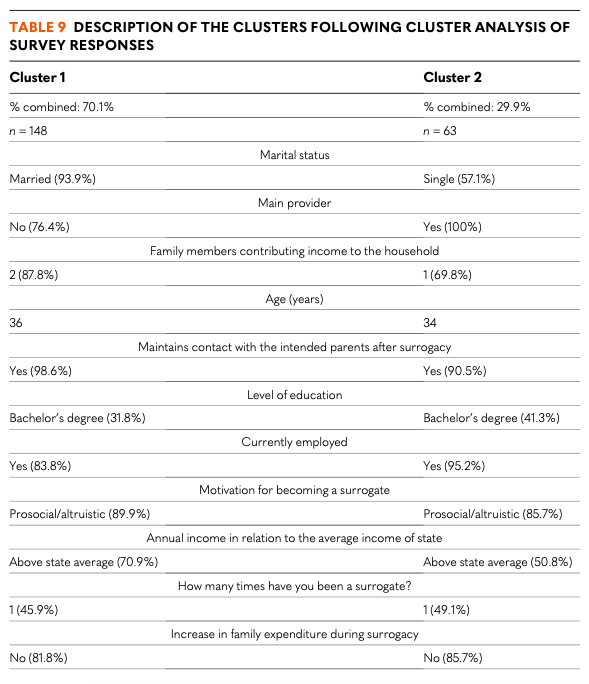

Finally, the results enabled the authors to group the majority of surveyed GCs in two distinct cohorts, shown in this table:

These two cohorts account for 91.3% of the GCs, and apart from marital status (‘Married’ in cohort 1 and ‘Single’ and cohort 2) and main provider status (‘No’ in cohort 1 and ‘Yes’ in cohort 2), they demonstrate similarities in terms of contact with IPs after pregnancy, educational status past high school, engaged in employment, and income above the average for the state.

Conclusions, Future Research, and Implications for European Policy

Based on these results the authors concluded that the majority of women who become GCs:

Do not have low socio-economic status

Have a medium to high level of education

Participate in the labor market

Have an income above the average for their state

Have medical insurance

Their primary motivation for surrogacy is prosocial or altruistic.

The results show that women who become GCs are not in a precarious or vulnerable situation. None of the variables introduced in the study corroborated this premise.

However, the study did find that 9.7% of respondents had become a GC for economic reasons, but the publication does not give details for these specific women. It would be interesting to know their demographics, support structures, education, and employment histories. Maybe they had 5 children of their own, and so the extra money was needed. Maybe their partner had recently lost their job.

It’s not necessarily ‘bad’ to become a GC for primarily economic reasons. As long as these women are still choosing to do this of their own accord without pressure or coercion.

Future research could specifically target GCs in the U.S. who did surrogacy for primarily financial reasons. Perhaps these women have valid reasons for wanting or needing the money, but they still have altruistic or prosocial tendencies. This survey did not allow for women to have multiple motivations for becoming GCs, so that could be explored in future research.

Also, it would be interesting to know these economically-motivated GCs’ experiences after surrogacy. In this study, 86% of GCs had overwhelmingly positive experiences with the IPs and their own families during the journey. How different, if at all, is this for women who initially choose to do this for economic reasons?

Another area of future research would be to survey GCs in less affluent countries where surrogacy is becoming more popular, such as Colombia and Mexico. The concerns about GC’s economic and educational status as well as their motivations are even more pronounced in these countries compared to the U.S., so this would be extremely important to understand and help maintain the ethical standards of surrogacy around the world.

Because the lead author is Spanish, I believe this research was done specifically for European policy makers, who are increasingly negative towards surrogacy, and in the case of Italy, have made it illegal domestically and internationally (https://www.babymoonfamily.com/original-articles/italy-attacks-surrogacy-rainbow-families).

Spain is culturally similar to Italy in terms of religion and conservative concepts of ‘family.’ In these countries, surrogacy is criticized by radical feminism and ultra-conservative Catholicism. These groups claim that surrogacy undermines some fundamental rights of women, without taking into account the prosocial and altruistic motivations that GCs have and is supported by this research.

Hopefully, more research with GCs everywhere surrogacy is legal can be done to convince policy makers and regulators that surrogacy can be safe, ethical, and amazing for all parties, even when compensation is involved. This will go a long way in helping to stop international surrogacy bans in other countries and allow rainbow families to grow and prosper.

References: