Why Do Women Become Gestational Carriers?

As a married gay man embarking on my first journey to fatherhood through IVF and surrogacy, there are a lot of questions. Through BabyMoon Family, I am working to document my personal experience, as well as write about topics related to the science, social perceptions, politics, and all interesting aspects of this fascinating process, especially focusing on issues for queer-identified men.

Although we are not yet at the point of matching with a gestational carrier (GC) in our journey, I have for some time been very interested in the persona of a woman who becomes a GC. Is there a typical woman who does this? What are her motivations for doing it? How do GCs view collaborating with queer male intended parents (IPs), like myself? In this article, I will dive into these questions to try and gain some understanding and empathy for these incredible women who make the dream of becoming parents a reality for so many people in the world.

First, a bit of vocabulary. The terms ‘surrogate’ and ‘gestational carrier’ (GC) are used interchangeably, but in my opinion the term GC is a more modern and preferred wording. However, I think it’s interesting to know the origins of these words. The word ‘surrogate’ is rooted in Latin ‘subrogare,’ which means ‘appointed to act in the place of.’ This equates to a form of substitution, especially a person deputizing for another in a specific role, in this case, the role of carrying and delivering a child (1). ‘Gestation’ is the period of time during which the fetus develops in the uterus of a woman. It begins with conception and ends with birth. The word originates from the Latin verb ‘gestare,’ meaning to bear (2). Given how the ideal relationship between the GC and IPs is a collaborative, supportive relationship, the term ‘surrogate’ is less appealing for me as it implies an ‘outsourcing.’ This outsourcing and assumed exploitation is often latched on to by anti-surrogacy groups and politicians as a way to vilify the journey. The term GC is much more accurate in that it describes the function of gestating the child, without implying that the IPs are not involved or that the GC is in any way exploited in the process.

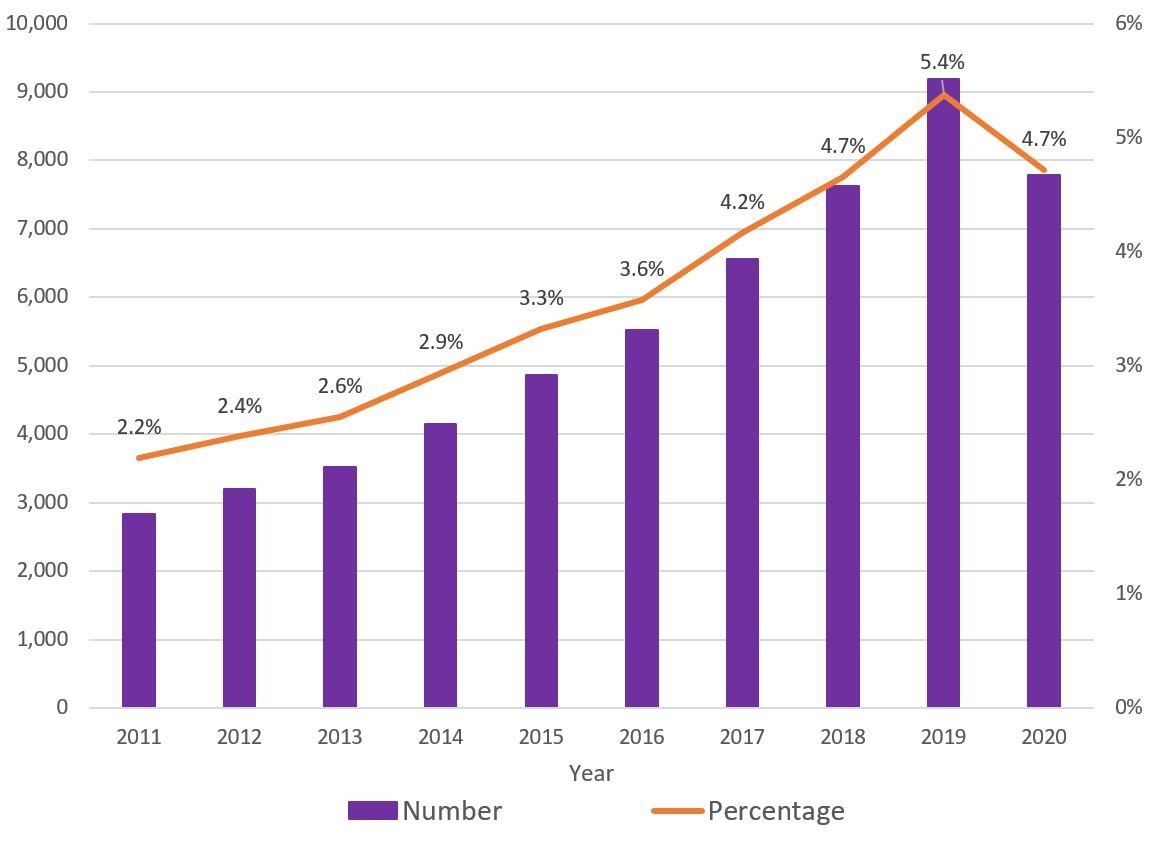

Before discussing some of the features and perspectives of GCs, I wanted to highlight some statistical trends in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), who collects and reports regularly on all assisted reproductive technology (ART) in the United States, the number of embryo transfer cycles that used a GC increased from 2,841 in 2011 to 9,195 in 2019, with a decrease in 2020 (7,786) attributed to the pandemic. The percentage of transfers using a gestational carrier among all ART cycles also increased, from 2.2% in 2011 to 5.4% in 2019, with a decrease in 2020 (4.7%) (3). These statistics are shown in the following figure:

Source: CDC (3)

Further substantiating the CDC data, a recent survey showed that nearly a quarter (23%) of Millennial women said that, if they found out they could not conceive naturally, they would consider surrogacy. Just 9 percent of Gen-X women said the same, so there are generational perceptions on surrogacy that are evolving as well (4).

But who are these women who become GCs? While it is not possible or accurate to distill these incredible women down to a few features, there are some qualities that are broadly shared across the group:

They like being pregnant.

They value family and children.

They had a positive exposure to GCs and the process of surrogacy earlier in their lives.

Before diving more into these three themes, I want to emphasize that one of the common traits not shared by the majority of GCs is the financial incentives. In the United States, the majority of surrogacy arrangements are commercial, meaning the GC is compensated financially. This is in contrast to the surrogacy arrangements in Canada and Europe, which are altruistic. Altruistic surrogacy only allows for reimbursement of expenses without any financial incentive.

In critiquing Netflix’s ‘The Surrogacy’ and its terrible portrayal of the process in Mexico (https://www.babymoonfamily.com/original-articles/netflix-the-surrogacy or https://medium.com/@babymoonfamily/netflixs-the-surrogacy-a-terrible-portrayal-of-surrogacy-that-comes-at-a-bad-time-b8e87ecf29dc), I wrote about how realistically challenging it is to qualify to be a GC and that the women cannot ‘need’ the money. This means that neither she, nor her partner or immediate family, can have any significant financial debts. The money cannot be integral to their income in order to support her or her family. This type of financial review is conducted for surrogacy arrangements in the United States prior to all the psychological and medical screening that is also required. Given this, GCs in the United States state that the financial compensation is a benefit, but it is not the primary motivation to be a GC. Given these strict financial, psychological, and medical qualifications, the vast majority of women do not qualify to be GCs. One agency stated that they receive about 400 applications a year, of which only about 1% are accepted (5). Within the framework of compensation not being in any way coercive given that she doesn’t need the money, I truly believe that GCs should be compensated given the risks and sacrifices they make in order to help others.

Like Being Pregnant

For a woman to qualify as a GC in the United States, she has to have had at least one successful and uneventful pregnancy. This is medically necessary in order to provide confidence to the IPs that she can carry a pregnancy to term. While previous normal pregnancies do not guarantee future success, it is a very good indication. For most GCs, they not only have had uneventful previous pregnancies, but also they have really enjoyed the time and experience of being pregnant. Given that all pregnancies are different, the range of ‘good’ to ‘bad’ pregnancies is vast. Some women have no nausea or vomiting at all, while others are unfortunate enough to be diagnosed with hyperemesis gravidarum, which is essentially intractable and severe vomiting during pregnancy that can result in weight loss and volume depletion (6). Nausea and vomiting are just one of the many potential negative effects that can come with pregnancy, but some women are fortunate enough not to experience these at all or much less severely than others. One quotation summed this up, with a GC claiming:

‘If I could have a million children, I would’ (4).

Value Family and Children

A second common theme among GCs is the priority of family and children in their own lives (7). Many state that children are the greatest gift and blessing. They cannot imagine a life without their own children, and so when confronted with a single person or couple who cannot conceive, they are motivated to help. GCs are also often moved by the idea that the child, the gift they will help deliver, will be so wanted by the IPs because of all the challenges they have had to endure and overcome to be parents. They want to help and show empathy and compassion for IPs, in a true act of kindness and love. A quote from one GC summed up this perspective:

‘I just want to show people that you can love others. It’s not always easy, but it’s important’ (4).

Positive Exposure to GCs

This third common theme amongst GCs is one that was most interesting to me. Many GCs have had positive exposure and been influenced by others in their lives who have been GCs. Some had relatives who needed GCs, others had known teachers in school who were GCs themselves, and many of us — myself included — were exposed to the idea through the TV show, Friends. In the show, Phoebe offers to carry triplets for her brother and his partner, and in doing so, the idea of a GC as a positive, caring, helpful, and incredible woman was introduced to millions of viewers across the United States.

One aspect of the GC perspective that is especially relevant for me and the community of BabyMoon Family is the view on queer male IPs. In contrast to heterosexual couples, single or partnered all-male IPs do not come to the process of surrogacy with any fertility ‘baggage.’ This means that they have not been made to feel inadequate or insecure by society for their lack of fertility, which is unfortunately the case for women. Some GCs have commented that this causes female IPs to bring some negativity — perhaps jealousy — to the relationship, while queer male IPs can sometimes more easily form profound and supportive connections with GCs, which enhances the experience for all parties involved (8).

Previous GCs have spoken to the incredible bonds they have formed with queer male IPs. One particularly moving sentiment was from a queer women, who shared the following very practical and lovely support for the LGBTQ+ community:

‘I matched immediately with two guys. I really wanted to do it for them, because we’re two women and without our sperm donor, we wouldn’t have our son; without me and the egg donor, they wouldn’t have their baby. So it felt like a good trade off’ (4).

Another GC has stated that she ‘fell in love’ with an IP who was a single gay man. In doing so and going through the journey together, she said that she had gained an ‘extended family’ as they and their families remain incredibly close to this day (4).

Reading these reflections from GCs on their positive and affirming relationship journeys with queer men was very uplifting for me. I have nothing but respect, admiration, and awe for women who become GCs. They are generous and are truly making an incredible impact on the world. I am very excited to continue on our journey and look forward to meeting and building a relationship with the woman who will change our lives forever.

References: