Science Says: International Gestational Surrogacy in the United States is Increasing

In this third installment of the BabyMoon Family Journal Club, I will be reviewing a recent article on the trend of international gestational surrogacy in the United States.

As an international intended father myself, this topic is extremely relevant to my own personal journey.

This article was published on January 1, 2024 in the journal Fertility and Sterility, and the title is International gestational surrogacy in the United States, 2014–2020 (Abstract only: https://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282(23)02142-8/fulltext).

As with previous journal club reviews, I will discuss the background, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusions of the manuscript. If you would like a copy of the full publication, feel free to email me at bryan@babymoonfamily.com.

Also, if you’d like to read the previous journal clubs, you can find them here:

Science Says: Gay Parents are Better than Straight Parents (https://www.babymoonfamily.com/original-articles/gay-fathers-better-than-straight-parents OR https://medium.com/@babymoonfamily/science-says-gay-parents-are-better-than-straight-parents-0d5846686af6)

Science Says: Being a GC During the Pandemic was Very Hard (https://www.babymoonfamily.com/original-articles/gc-pandemic-study OR https://medium.com/@babymoonfamily/science-says-being-a-gc-during-the-pandemic-was-very-hard-d6c9d865350c)

Background

International gestational surrogacy exists and thrives for several reasons in the United States:

Illegality of commercial surrogacy in many countries

Cost-prohibited domestic surrogacy in other countries were it is legal

Political, social, and cultural context of other countries were single people and LGBTQ+ are often not allowed to access ART

Medical and legal expertise in the U.S.

Previous studies have looked at the amount of intended parents (IPs) coming from abroad to work with gestational carriers (GCs) in the U.S. One study found that between 1999 and 2013, approximately 16% of IPs using a GC in the U.S. were not residents of America.

This study aims to update these data with trends with international IPs working with GCs in the U.S. from 2014 to 2020.

Methodology

The authors leveraged the fact that the U.S. keeps a fairly robust database related to ART across the country. The Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) Clinic Outcome Reporting System (CORS) collects data from approximately 79% of ART clinics in the United States, which accounts for over 90% of reported IVF treatment cycles in the U.S.

SART CORS then verifies and reports these ART data to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in compliance with the Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act of 1992 (Public Law 102–493).

Given that in many ways — especially when it comes to healthcare — the United States can be a significantly compartmentalized and fractured system, it is interesting that data related to ART is actually well organized and collected, and this makes for a valuable data set for research and trends in the ART industry.

Results

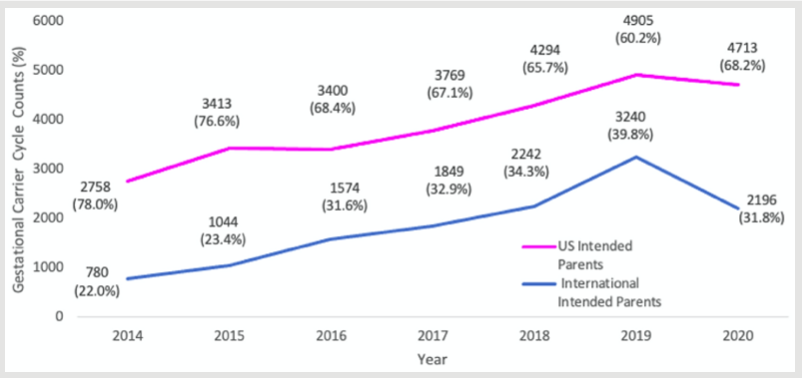

Between 2014 and 2020, there were 40,177 GC cycles involving an embryo transfer, 32% of which were for international IPs.

The total number of GC cycles increased for both domestic and international IPs from 2014 to 2019, but the increase was proportionally more significant for international IPs:

Domestic IPs went from rom 2,758 to 4,905 cycles.

International IPs went from 780 to 3,240 cycles.

These data and trends are shown in the figure below:

Both groups experienced a decline in 2020, with the decline being more marked in the international IP group. This was obviously attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, with travel restrictions to and from the U.S. having a more significant impact on international IPs.

In terms of other notable demographic differences, the database showed that international IPs were more likely to be male (41.3% vs. 19.6%; P<.0001), be older than 42 years (33.9% vs. 26.2%; P<.0001), and identify as Asian race (65.6% vs. 16.5%; P<.0001).

In terms of reproductive reasons for using a GC, international IPs were more likely to use a GC because of the absence of a uterus than U.S. IPs (43.1% vs. 23.4%; P< .0001).

GCs selected by international IPs were more commonly younger than 30 years (42.8% vs. 29.1%; P< .0001) and a larger proportion identified as Hispanic race compared with those selected by U.S. IPs (28.6% vs. 11.7%; P<.0001).

Geography within the U.S. also was different between international and domestic IPs. Of all GC cycles involving international IPs, 75.3% were performed at clinics in either California (64.8%) or Oregon (10.5%). The next three most common states were Connecticut (3.6%), Nevada (3.6%), and Illinois (2.7%). In comparison, GC cycles done for domestic IPs were more evenly distributed among states with the two most common states being California (24.5%) and Texas (10.0%).

International IPs more frequently used donor oocytes (67.1% vs. 43.5%; P<.0001), an oocyte source less than 35 years of age (67.6% vs. 58.9%; P< .0001), and adjunct fertility treatments or techniques, such as intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) (72.8% vs. 55.4%; P< .0001) and preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGT) (79.0% vs. 55.8%; P< .0001). International IPs were less likely to have two embryos transferred at once compared with U.S. IPs (23.2% vs. 27.5%; P< .0001).

The map below shows the countries of origin for international IPs working with GCs in the U.S. during this time. The 5 most common countries of origin were China (41.7%), France (9.2%), Spain (8.5%), the United Kingdom (5.3%), and Israel (5.0%).

However, the map does illustrate that there is also participation from international IPs from Argentina, Australia, and countries on all continents.

Discussion and Conclusions

Beside clearly showing that the trend for international IPs to work with GCs in the United States is increasing, these data also provide some interesting insights into who these international IPs are and how they are approaching the process.

Demographics of international IPs seem to reflect queer men:

The demographics of international IPs are largely over 40 year old men whose main reason for pursuing surrogacy is not having a uterus. This sounds like queer men. This is interesting as the data from SART CORS does not collect information on sexual orientation, but it would be an interesting area of future research to explore how many and what proportion of international — as well as domestic IPs — are queer intended fathers.

Science shows international IPs are more cautious:

The information on international IPs from this data set demonstrates that these IPs are more inclined to spend upfront on the process to optimize for success. International IPs are more inclined to use ICSI and PGT as well as select younger egg donors and GCs. They are also less likely to implant more than one embryo. These all suggest that because pursuing IVF and surrogacy in the U.S. is such an expensive endeavor, international IPs are willing to select additional testing, donors, and GCs that are more likely to ensure a successful outcome.

Geography shows international IPs want the most surrogate-friendly state:

Overwhelmingly, international IPs preferred California for their GC. This is not surprising in that California offers the most progressive and strongest legal framework for surrogacy. This is especially important for international IPs, as the pre-birth orders for parentage in California allow for faster document processing, passport retrieval, and ability for international parents to get back to their home country. The expense of travel and an extended stay in the U.S. is another aspect to international gestational surrogacy arrangements that seems to be reflected in this state preference.

Interestingly, I would say that from my personal experience, each of these three components appears to be true. I am a 41 year old gay man who has opted for the most comprehensive clinic testing. My husband and I are also strongly considering California for our GC, even though there is currently a premium for California GCs given their high demand. So, it’s fascinating that our own experience is reflected in the data from the last decade regarding international IPs working in the U.S.

From a BabyMoon Family perspective, I would love for more research and detailed information to be collected and shared regarding the sexual orientation of IPs. Also, it would be great if more information and research could be done on the motivations for international IPs to pursue surrogacy in the U.S. Although the authors hypothesize that the legal, social, cultural, and medical aspects of international IPs home countries compared to the U.S. are several factors that could be influencing this trend, it would be great to gather more information on the real reasons why. Also, the U.S. is not the only destination for international gestational surrogacy. Similar research should be done for Mexico, Colombia, Cyprus, and other countries where commercial gestational surrogacy is pursued by international IPs.

There is so much more to discover and describe with the growing trend of international gestational surrogacy, and the BabyMoon Family Journal Club will continue to explore the science and literature as it is published.